|

|

Accountability and Participation: Report on training on PRA and Social Accountability in East and Southern Africa, 6th – 11th October 2013

|

Barbara Kaim

|

|

Background

Something important happened in Zimbabwe in October 2013. While we could be referring to discussions in the parliament related to the health budget; or preparations for a regional heads of state meeting where leaders will be talking about the major challenges facing our region in the coming year; or equally as relevant to issues of health— the fact that the first summer rains began, heralding the start of the planting season, but this is not what this article is about. In this case, we are talking about a meeting that took place in Chengeta, 70kms north of Harare, where 30 people, representing 18 organisations from 6 countries in the east and southern African region, met for 4 days to discuss and deepen our understanding on ways to strengthen primary health care through improving public involvement and ensuring health service accountability. |

This training was organized by the Training and Research Support Centre (TARSC) in Zimbabwe, through COPASAH and the Regional Network for Equity in Health in east and southern Africa (EQUINET) with support from the Open Society Foundation. Using existing EQUINET training materials, methodologies and capacities on Participatory Reflection and Action (PRA) and COPASAH materials and capacities on community monitoring and social accountability, this partner-ship brought together processes of social account-ability being explored in COPASAH with EQUINET‘s focus on strengthening health systems at the community and primary care level as important for increased equity. The meeting was facilitated by TARSC (Barbara Kaim), UNHCO (Robinah Kaitiritimba) and Lusaka District Health Management Team (Clara Mbwili and Adah Zulu). It brought together community health activists, civil society organisations, health workers, academics and researchers from Kenya, South Africa, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe, all of whom had a range of experiences in participatory approaches and social accountability in health.

The meeting aimed to explore how PRA approaches could be used to raise community voice in strengthening the functioning and resourcing of primary health care (PHC) systems in the region. This proved to be quite a task, challenging us to move out of our familiar ‗silos‘to engage with new approaches and terminology (for some, words such as ‗rights holder ‘and duty bearer ‘were quite new; for others, it was the first time they were being introduced to concepts of the PRA approach), as well as new ways of interacting with community, with the way we build and use knowledge, and how this all relates to our ideas of change.

We began our discussions by reflecting on the extent to which our health systems are people-centered and how this, in turn, impacts on issues of accountability. Taking the example of a teenage girl in her 3rd trimester coming to the clinic for the first time, we developed a human sculpture‘of how we think the health services in our countries would currently respond. How would she be treated at the clinic? How would the family and community support her? What we saw was that the pregnant teenager was power-less in ensuring that her health needs were met. Resources to support the local health workers were far away, with decisions coming from the capital of the city or from boardrooms of international agencies such as the IMF or World Bank. Figure 1 shows the actors in the human sculpture pointing to whom they thought they were accountable. The young girl is isolated.

The meeting aimed to explore how PRA approaches could be used to raise community voice in strengthening the functioning and resourcing of primary health care (PHC) systems in the region. This proved to be quite a task, challenging us to move out of our familiar ‗silos‘to engage with new approaches and terminology (for some, words such as ‗rights holder ‘and duty bearer ‘were quite new; for others, it was the first time they were being introduced to concepts of the PRA approach), as well as new ways of interacting with community, with the way we build and use knowledge, and how this all relates to our ideas of change.

We began our discussions by reflecting on the extent to which our health systems are people-centered and how this, in turn, impacts on issues of accountability. Taking the example of a teenage girl in her 3rd trimester coming to the clinic for the first time, we developed a human sculpture‘of how we think the health services in our countries would currently respond. How would she be treated at the clinic? How would the family and community support her? What we saw was that the pregnant teenager was power-less in ensuring that her health needs were met. Resources to support the local health workers were far away, with decisions coming from the capital of the city or from boardrooms of international agencies such as the IMF or World Bank. Figure 1 shows the actors in the human sculpture pointing to whom they thought they were accountable. The young girl is isolated.

|

|

People need to be empowered; we must know our rights and claim them. We must not sit back and take things lying down; we need to take ownership of our facilities and of our health. If I know that the clinic is open from 7.30am – 4pm, I should not have to wake up at 4am and risk my life to get a place in the queue. The duty bearers take advantage of the fact that most people who make use of primary care facilities are poor and uneducated, so they do whatever they like.

- A Workshop Participant

- A Workshop Participant

When we moved the human sculpture around to reflect what we thought a people-centered health system should look like (Figure 2), we saw that the teenager was now at the centre of a caring community, with the health workers linked to and listening to her needs, and with resources flowing from the finance and health ministry’s to the local clinic. There was a much greater sense of accountability – both in terms of service delivery and in the allocation of resources - from the top echelons of the system down to the clinic to meet the needs of the young girl.

This activity vividly pointed to the fact that building a people-centered health system is not simply a technical question, but needs to build of on the power of individuals, communities, health workers and others to create the changes needed to ensure people‘s right to health. This is especially true in a region where, despite encouraging signs of overall progress in health, there are still wide inequalities between social groups and between countries, with poorer households and especially women and children being the most negatively affected (EQUINET Regional Equity Watch 20122). It is here that the intersection between building people‘s power and increased social accountability becomes clear.

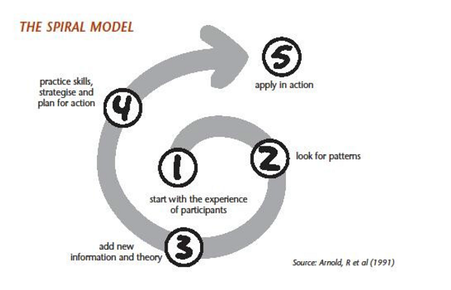

To explore this further, we looked at how learning and change takes place. Reviewing the Spiral Model as a tool to understanding PRA (Figure 3), we saw that the starting point of any empowering process is people‘s own knowledge and experiences, leading to a group analysis of these experiences, identifying new information and skills, and then planning for action. The PRA process is like a spiral with regular cycles of reflection and action, whereby communities can learn from their successes and continue to find better solutions to their difficulties, thus moving closer each time to achieving positive change in their lives.

This activity vividly pointed to the fact that building a people-centered health system is not simply a technical question, but needs to build of on the power of individuals, communities, health workers and others to create the changes needed to ensure people‘s right to health. This is especially true in a region where, despite encouraging signs of overall progress in health, there are still wide inequalities between social groups and between countries, with poorer households and especially women and children being the most negatively affected (EQUINET Regional Equity Watch 20122). It is here that the intersection between building people‘s power and increased social accountability becomes clear.

To explore this further, we looked at how learning and change takes place. Reviewing the Spiral Model as a tool to understanding PRA (Figure 3), we saw that the starting point of any empowering process is people‘s own knowledge and experiences, leading to a group analysis of these experiences, identifying new information and skills, and then planning for action. The PRA process is like a spiral with regular cycles of reflection and action, whereby communities can learn from their successes and continue to find better solutions to their difficulties, thus moving closer each time to achieving positive change in their lives.

When reflecting on the Spiral Model, we acknowledged that:

Based on this understanding, participants went on to review a number of PRA tools to deepen their understanding of how to strengthen community and health worker voice, level of organization and demand for improved resourcing and functioning of the primary health care system. The programme took us through skills training on how to develop a social map as a way to draw on people‘s understanding of their environment, ways of identifying and prioritizing health needs (Figure 4) and the causes underlying health problems, how to improve relations between health workers and community (Figure 5), as well as sharing experiences and challenges on how rights holders and duty bearers can ensure people‘s rights are met. We also spent time looking at how to identify gaps in health service resourcing and delivery, moving toward action planning in overcoming these barriers. As we moved toward the final sessions of the training, we looked at a number of accountability and monitoring tools, including the community score card, wheel chart and progress markers.

- Without the involvement of those who need health services, services may not meet specific needs;

- People cannot demand services and accountability if they have not explored what they want and what they are entitled to;

- This process needs to be cognizant of power dynamics and power inequities at local level in order to ensure the participation of disadvantaged groups;

- Active community participation in the functioning of health services can offer greater accountability and improved responsiveness of services;

- Accountability mechanisms can support and improve interactions between communities and frontline service providers and can lead to alliances that negotiate with higher level authorities for improvement; and

- Ultimately, accountability processes should impact on improved service delivery and greater access to resources (such as medicines, personnel, transport) at primary care level

Based on this understanding, participants went on to review a number of PRA tools to deepen their understanding of how to strengthen community and health worker voice, level of organization and demand for improved resourcing and functioning of the primary health care system. The programme took us through skills training on how to develop a social map as a way to draw on people‘s understanding of their environment, ways of identifying and prioritizing health needs (Figure 4) and the causes underlying health problems, how to improve relations between health workers and community (Figure 5), as well as sharing experiences and challenges on how rights holders and duty bearers can ensure people‘s rights are met. We also spent time looking at how to identify gaps in health service resourcing and delivery, moving toward action planning in overcoming these barriers. As we moved toward the final sessions of the training, we looked at a number of accountability and monitoring tools, including the community score card, wheel chart and progress markers.

|

It has contributed tremendously towards my morale, I am now confident about my job. I feel ignited to do more, because I know more‖

-A Workshop Participant ―The workshop has given me hope. I really was battling with how I mentor the committees, after the workshop I got home and drafted a mentoring programme, which I was struggling with before ‖ - A Workshop Participant |

ABOUT AUTHORS

Barbara Kaim with input from Robinah Kaitiritimba and Frederick Okwi from UNHCO.

Barbara Kaim is working as Programme Manager at Training and Research Support Centre (TARSC), Zimbabwe.

To know more about TARSC please CLICK HERE

This article was authored by Barbara Kaim, with input from Robinah Kaitiritimba and Frederick Okwi from UNHCO. With thanks to facilitators and all participants who attended the training for your enthusiasm, hard work and amazing insights drawn from such a wide range of experiences.

Barbara Kaim with input from Robinah Kaitiritimba and Frederick Okwi from UNHCO.

Barbara Kaim is working as Programme Manager at Training and Research Support Centre (TARSC), Zimbabwe.

To know more about TARSC please CLICK HERE

This article was authored by Barbara Kaim, with input from Robinah Kaitiritimba and Frederick Okwi from UNHCO. With thanks to facilitators and all participants who attended the training for your enthusiasm, hard work and amazing insights drawn from such a wide range of experiences.