|

|

Community Based Monitoring on

Quality of Care in Family Planning Services

Quality of Care in Family Planning Services

Experiences of Family Planning Programme from 50 selected villages of 10 districts of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, India mapped through CBM approach highlight concerns of lack of quality of care and informed choice. The experiences suggest accountability issues and challenges in terms of gaps in service delivery of family planning.

|

NIBEDITA PHUKAN

|

Women Participating in Focused Group Discussion

Women Participating in Focused Group Discussion

Quality of Care and informed choice have long been areas of concern in India’s Family Planning Programme (FPP). Family Planning within the context of health is one of the national flagship programmes of the Government of India (GoI) which was started in 1951 and has a long and chequered history. An obsessive fear of explosive population growth led to the introduction of coercive components like targets, incentives and penalties for the community as well as the health worker in the FPP during later decades. However, the programme was often reduced to provision of female sterilisation. In rapidly conducted sterilisation camps the quality of surgical procedures was poor. After signing the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development (PoA- ICPD, 1994), the GoI made many changes in the way the family planning programme was designed and implemented. Method specific targets were abandoned; standard operating procedures¹ and quality assurance mechanisms were introduced. Even though the GoI shifted its programme focus from female sterilization to an approach focusing on birth spacing and temporary methods, India being a large county, the programmes delivered on the ground can be very different from policy intentions. There is a need to understand whether couples especially women have access to high quality, need based family planning services which is the true intention of the family planning programme. Concerned over the lack of quality and informed choice in the family planning programmes, nine Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) with technical help from Centre for Health and Social Justice (CHSJ) undertook Community Based Monitoring (CBM)² on family planning services in 50 selected villages of ten districts of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar . The ten districts in Bihar³ and Uttar Pradesh for the CBM process were selected on the basis of three criteria:

- Low level of awareness on family planning services in the selected districts.

- Higher concentration of marginalised communities.

- Strong presence Health Watch Forum. 4

Initiating the Process: Building Capacities of women

The entire process of CBM was led by women selected from the community in the villages. These women were given orientation on the objectives of the process and provided trainings in the perspectives of the tools and the process of administering it.

Community meetings and focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted in each of the ten villages. Women using contraceptives (married women who have used Intra Uterine Device (IUD), or contraceptive pill or sterilization or injectables as a method of family planning) from 2011 through 2014 were identified during the FGDs. Additional information was accessed from the records maintained by Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs). Interviews were conducted with women users and women who are expecting a visit by the health service providers to conduct family planning counseling, or are using services in the districts. The women’s age group was 19-45 years.

Identification of issues and simplification of tools

The issues were identified under the broad framework: quality of care, cient identification, counseling, information and choice given to the women, quality of services, follow-up and management and level of coercion that includes incentives. From the service providers, the data was collected under the themes like knowledge of family planning methods, counseling provided to clients on IEC, options available, preparedness of facility to provide family planning services, quality of clinical services, follow-up and management, and targets given (if any).

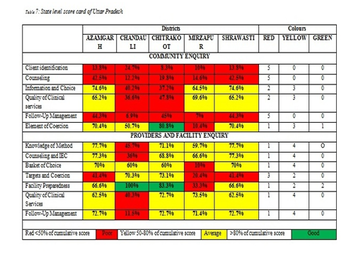

Data Collection, analysis and preparation of report cards

After gathering the information through the FGDs, interviews with family planning users, interviews with ASHAs and Medical Officer In-Charge (MOIC), and facility observation were conducted. Scores were given to each of the conducted inquiry, and a community scorecard was processed. Data triangulation was done by identifying and clubbing the responses from various tools under the themes/issues that were identified from the reference guidelines, documents and manuals consulted for developing the tools. Cumulative scoring was calculated for each of the themes and later percentage was calculated. The results were colour coded in order to obtain final results in the form of a traffic light. Reverse scoring was done in case of questions related to coercion.

The entire process of CBM was led by women selected from the community in the villages. These women were given orientation on the objectives of the process and provided trainings in the perspectives of the tools and the process of administering it.

Community meetings and focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted in each of the ten villages. Women using contraceptives (married women who have used Intra Uterine Device (IUD), or contraceptive pill or sterilization or injectables as a method of family planning) from 2011 through 2014 were identified during the FGDs. Additional information was accessed from the records maintained by Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs). Interviews were conducted with women users and women who are expecting a visit by the health service providers to conduct family planning counseling, or are using services in the districts. The women’s age group was 19-45 years.

Identification of issues and simplification of tools

The issues were identified under the broad framework: quality of care, cient identification, counseling, information and choice given to the women, quality of services, follow-up and management and level of coercion that includes incentives. From the service providers, the data was collected under the themes like knowledge of family planning methods, counseling provided to clients on IEC, options available, preparedness of facility to provide family planning services, quality of clinical services, follow-up and management, and targets given (if any).

Data Collection, analysis and preparation of report cards

After gathering the information through the FGDs, interviews with family planning users, interviews with ASHAs and Medical Officer In-Charge (MOIC), and facility observation were conducted. Scores were given to each of the conducted inquiry, and a community scorecard was processed. Data triangulation was done by identifying and clubbing the responses from various tools under the themes/issues that were identified from the reference guidelines, documents and manuals consulted for developing the tools. Cumulative scoring was calculated for each of the themes and later percentage was calculated. The results were colour coded in order to obtain final results in the form of a traffic light. Reverse scoring was done in case of questions related to coercion.

Findings reveal that

Challenges and Gaps at Facility Level

- The focus of intervention was solely on women who had two or more children.

- ASHAs did not provide any detailed information on spacing methods, except for sterilisation.

- Family planning service providers did not identify newly married couples and also failed to understand the needs of the newly-weds in spacing methods.

- Method-specific counselling was poor in all the districts.

- Physical and pelvic examination of many women was not conducted prior to IUD insertion.

- Women were not counselled on the side effects/health problems that could occur after sterilisation operation.

- Many sterilisation users reported that that the consent form was not read out to them and they were not told what was written in the consent form.

- The women said that ASHAs did not pay visits after the selection of any family planning methods.

- ASHAs hardly turned up for counselling in case the family planning users felt discomfort after using any of the methods.

- There were very few women who were provided with sterilisation certificates and given written discharge slips describing the date of insertion of IUD and duration of the insertion.

- ASHAs did not tell many Oral Contraceptive Pills (OCP) users what they should do if they forgot to take a tablet.

Challenges and Gaps at Facility Level

- The Primary Health Centres/ Community Health Centres were not well-equipped to provide family planning services and no family planning counsellors were available in the PHCs.

- Lack of regular supply of family planning services to the facility.

- ASHA and Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANMs) reported that the administration often failed to provide them with the needed medical supplies and material in order to meet the family planning needs of the population they catered.

- ASHA workers said none of the authorities helped them in redressal of grievances of the community. ASHAs shared their problems and opined that their opinions were not heard by higher authorities.

- The MOICs agreed that target for sterilisation was set. The target set ranged from 200-400 to 1000 in a year, in all the ten districts.

- Lack of staff to provide family planning services.

- Inadequate storage and stock system for contraceptive methods in the hospital.

- No specific family planning counsellor in any of the PHCs.

Discussion with health care service providers during CBM

Discussion with health care service providers during CBM

Follow-up of the Enquiry: Public Dialogue Process

Public dialogues empower the community to speak about the issues that they face. This is the most crucial CBM processes of engagement. The findings with district level report cards from the CBM process and testimonials were shared in the district and state level public dialogues to the health service providers, media, lawyers, Panchayati Raj Institution (PRI) members, CSO partners, INGOs and community members. This was followed by responses from health officials, thus providing an opportunity for people to demand corrective action by health functionaries.

Conclusion: Accountability Issues and Challenges

In all the districts, where this process was initiated, the partner organisations are in conversation with local health service providers,but there is a lack of a common ground that is hindering negotiation for change in family planning services. The training and content of training provided by the service providers is inadequate. There is inappropriate use of terms and definitions of health, human rights and entitlements. The state-level targets for family planning are a major challenge that hinder changes in quality of care and informed choice in family planning. From this initiative and other experiences it discerns that there is an irrational emphasis on long acting and permanent methods in the Indian Family Planning Programme with no focus on delaying first birth and spacing between the first two births. The family planning service providers’ performances are incentivized. Where incentives are there, bringing about quality service is a distant dream.

From this CBM process it surfaced that there was a strong gap in service delivery of family planning. It discerns that family planning services are a matter of self choice and should be put into use through proper motivation and counselling and not as a matter of compulsion.

Public dialogues empower the community to speak about the issues that they face. This is the most crucial CBM processes of engagement. The findings with district level report cards from the CBM process and testimonials were shared in the district and state level public dialogues to the health service providers, media, lawyers, Panchayati Raj Institution (PRI) members, CSO partners, INGOs and community members. This was followed by responses from health officials, thus providing an opportunity for people to demand corrective action by health functionaries.

Conclusion: Accountability Issues and Challenges

In all the districts, where this process was initiated, the partner organisations are in conversation with local health service providers,but there is a lack of a common ground that is hindering negotiation for change in family planning services. The training and content of training provided by the service providers is inadequate. There is inappropriate use of terms and definitions of health, human rights and entitlements. The state-level targets for family planning are a major challenge that hinder changes in quality of care and informed choice in family planning. From this initiative and other experiences it discerns that there is an irrational emphasis on long acting and permanent methods in the Indian Family Planning Programme with no focus on delaying first birth and spacing between the first two births. The family planning service providers’ performances are incentivized. Where incentives are there, bringing about quality service is a distant dream.

From this CBM process it surfaced that there was a strong gap in service delivery of family planning. It discerns that family planning services are a matter of self choice and should be put into use through proper motivation and counselling and not as a matter of compulsion.

|

|

ABOUT AUTHORS

Nibedita Phukhan works as Programme Officer, Research at the Centre for Health and Social Justice (CHSJ) India. Her area of work focuses majorly on Reproductive Sexual and Health Rights and Maternal Health Rights. She also coordinates the communication platforms such as Reproductive Health Observatory and National Coalition Against Two Child Norm & Coercive Population Policies.

To know more about the work of CHSJ please visit, www.chsj.org.

Nibedita Phukhan works as Programme Officer, Research at the Centre for Health and Social Justice (CHSJ) India. Her area of work focuses majorly on Reproductive Sexual and Health Rights and Maternal Health Rights. She also coordinates the communication platforms such as Reproductive Health Observatory and National Coalition Against Two Child Norm & Coercive Population Policies.

To know more about the work of CHSJ please visit, www.chsj.org.